- emergent phenomena

- Posts

- Stop rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic

Stop rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic

Be the iceberg instead

Have you ever felt blindsided by something you read in the news, only to later learn information that made the event feel inevitable?

So has Donella H. Meadows. “If the news did a better job of putting events into historical context,” she writes in Thinking in Systems: A Primer, “we would have better behavior-level understanding, which is deeper than event-level understanding.”

When an event happens, in others words, we should ask not only what happened but seek to understand the long-term behavior that led to this outcome. Has the event happened before? What structures might be causing this to happen?

“Long-term behavior provides clues to the underlying system structure,” Meadows writes. “And structure is the key to understanding not just what is happening but why.”

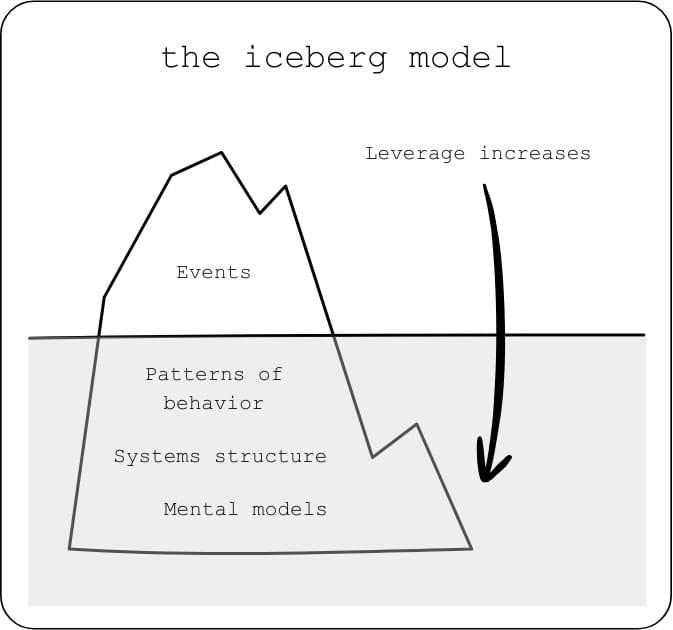

To map out the different levels of understanding, we can use the iceberg model.

Systems thinking iceberg

The systems thinking iceberg consists of four levels: events, patterns of behavior, system structure, and mental models. The event is visible above the water; all else is submerged.

emergent phenomena/Donella H. Meadows Project

Starting from the top, we can ask ourselves a series of questions to understand what’s happening under the water. For example:

Events: What is happening?

A train derails outside the bucolic college town of Blacksmith, Ohio, spilling Nyodene derivative and leading to an Airborne Toxic Event.1

Patterns of behavior: What trends are there over time?

Rates of Airborne Toxic Events; rates of train derailments (1,300 per year, according to USAFacts)

Systems structure: How are the parts related? What influences the patterns?

Our chemical industry requires toxic intermediaries and byproducts to be shipped all over the US.

Mental models: What values, assumptions, and beliefs shape the system?

A disaster such as this is unlikely to happen in my community. A life of material comfort requires me to accept disasters such as this one.

Once we’ve donned our scuba suits and descended to the mental model level, we’ll have a good basis for understanding the event’s driving forces. From there, we can start to grasp around for leverage points.

Where to intervene

In the simplified iceberg model, leverage–or the potential for small changes to massively impact behavior–increases the deeper we go. In reality, there are a dozen places to intervene in a system.

People tend to focus on numbers such as hourly rates, speed limits, and calories. But Meadows ranks this leverage point as the least effective, likening it to rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. If the conditions that shaped the system persist, the system’s behavior will persist as well.

Information flows rank in the middle of Meadows’s list. As communicators, this is the level many of us are working at. The who, what, how of a message are all components of an information flow. Is someone not receiving a message they need? Or could the message they’re receiving be the wrong one?

If we can manage to intervene at the levels of system goals and paradigms, these are among the most potent points of leverage.

How to apply it

If you’re trying to change someone’s opinion, for example by writing an op-ed, getting to the “mental model” depth of the iceberg model is critical. You need to get clear on what people believe before you can speak to those beliefs.

If needed to clarify your own perspective, model the system. “We change paradigms by building a model of the system, which takes us outside the system and forces us to see it whole,” Meadows writes.

Lastly, I’ll share a tip I picked up from Tamsen Webster, TEDxNewEngland idea strategist and author of Find Your Red Thread: surface the warrants. We often leave the justification for why evidence supports a claim (aka the warrant) implicit. Maybe because that’s how we’re used to seeing evidence presented, or perhaps the justification seems too obvious. But in leaving this part out, we’re asking our audience to fill in the blanks—and that’s just another opportunity to lose them.

I think this is why working with models—even simple ones like this one—can be so productive: they force us to make explicit the assumptions we often keep buried.

This museum of Titanic memorabilia is housed inside a jewelry store in Indian Orchard, MA (h/t Alla Katsnelson).

In addition to White Noise, the example above is loosely based on this op-ed by Joel Tickner et al. about the 2023 Norfolk Southern chemical spill in East Palestine, Ohio.

The iceberg model exists in many forms around the web. I primarily referenced this one from the Donella H. Meadows Project; Ecochallenge.org has another good one.

Hi! I’m Alex. I write about scientific research for nonprofits, universities, and brands. I also help experts communicate their own research. Learn more about my work or connect with me on LinkedIn.

Enjoying emergent phenomena?

1 DeLillo, Don. White Noise. Viking Press, 1985.